Neural Networks

2026-01-29

Sources

Content derived from: J&M Ch. 6

Part 1: Foundations of Neural Networks

Neural networks emerged from decades of research on connectionist computation

- Early foundations: McCulloch & Pitts (1943), Hebb (1949), Turing (1948)

- Turing’s insight: Complex behaviors emerge from many simple interacting units

- The connectionist paradigm: computation through distributed, parallel processing

Neuron

Perceptron

Revolution

The perceptron was the first learnable neural architecture

- Rosenblatt (1958) formalized learning from labeled examples

- Update rule adjusts weights based on prediction errors:

\[ \mathbf{w} \leftarrow \mathbf{w} + \eta (y - \hat{y}) \mathbf{x} \]

- Enabled learning of linear decision boundaries in input space

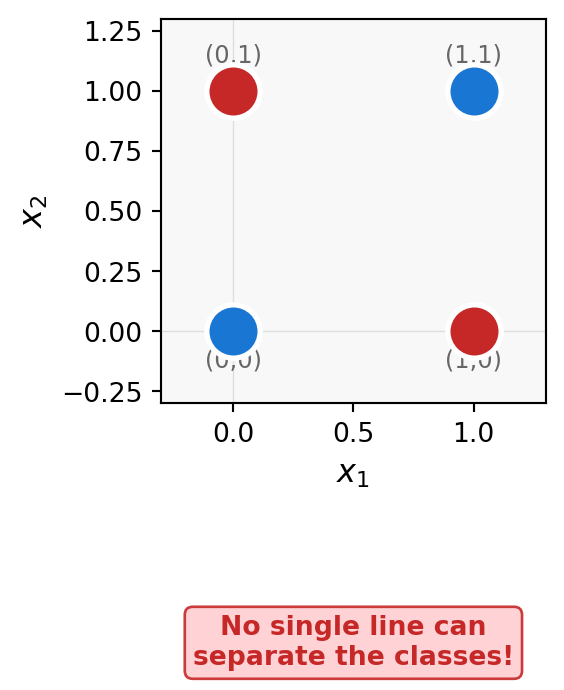

Why XOR breaks the perceptron

Solution: Add a hidden layer to create a non-linear decision boundary.

Backpropagation enabled training of multi-layer networks

- Rumelhart, Hinton, and Williams (1986) introduced error backpropagation

- Uses the chain rule to compute gradients through layers:

\[ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \theta} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{a}} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{a}}{\partial \theta} \]

- Allowed training networks with hidden layers, overcoming perceptron limitations

Modern architectures build on these foundational principles

- Hierarchical representation learning extracts increasingly abstract features

- Non-linear function approximation enables modeling complex relationships

- Scalability through parallelization and specialized hardware (GPUs, TPUs)

Applications span:

- NLP: machine translation, question answering, text generation

- Vision: object recognition, image segmentation

- Reinforcement learning: game playing, robotics

A neural network is a computational graph of interconnected processing units

- Each neuron computes a weighted sum of inputs plus bias, then applies an activation:

\[ h = f(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x} + b) \]

- \(\mathbf{w}\): weight vector (learned parameters)

- \(\mathbf{x}\): input vector

- \(b\): bias term

- \(f\): nonlinear activation function

Networks are organized into layers with distinct roles

- Input layer: Receives raw features (e.g., word embeddings)

- Hidden layers: Learn intermediate representations

- Output layer: Produces predictions (often via softmax)

Feedforward networks process information in one direction only

- Data flows from input → hidden → output with no cycles

- Each layer’s output becomes the next layer’s input

- The entire computation is a composition of functions:

\[ \hat{y} = f^{[L]}(f^{[L-1]}(\cdots f^{[1]}(\mathbf{x})\cdots)) \]

Recurrent networks can model sequential dependencies through cycles

- Allow information to persist across time steps

- Hidden state \(\mathbf{h}_t\) encodes history of previous inputs

- Essential for language modeling, speech recognition, time series

Neural network computation is fundamentally linear algebra

- Inputs, parameters, and activations are vectors and matrices

- Core operation: matrix-vector multiplication plus bias

\[ \mathbf{z} = \mathbf{W}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b} \]

- Dimensions must align: if \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d\) and \(\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times d}\), then \(\mathbf{z} \in \mathbb{R}^m\)

Dot products measure vector similarity

\[ \mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{b} = \|\mathbf{a}\| \|\mathbf{b}\| \cos(\theta) \]

Neural networks use dot products to measure relevance between vectors

Matrix multiplication computes all pairwise dot products

- If \(\mathbf{Q} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}\) and \(\mathbf{K} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times d}\), then:

\[ (\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^\top)_{ij} = \mathbf{q}_i \cdot \mathbf{k}_j \]

One matrix multiply computes all 12 similarities in parallel!

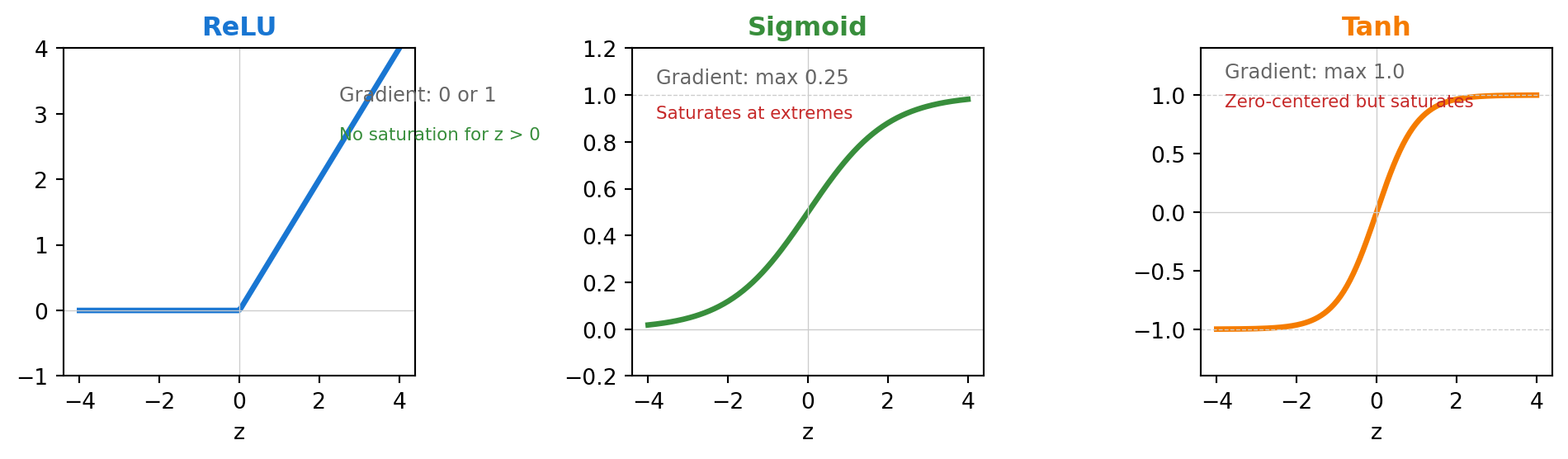

Activation functions introduce essential nonlinearity

After computing \(\mathbf{z}\), we apply an activation function elementwise:

\[ \mathbf{h} = \phi(\mathbf{z}) \]

Activation function shapes determine gradient flow

Why ReLU dominates: Constant gradient (1) for positive inputs prevents vanishing gradients in deep networks.

The softmax function converts scores to probabilities

- Transforms a vector \(\mathbf{z}\) into a probability distribution:

\[ \operatorname{softmax}(z_i) = \frac{\exp(z_i)}{\sum_{j=1}^d \exp(z_j)} \]

- Guarantees: \(\sum_i \operatorname{softmax}(z_i) = 1\) and \(0 < \operatorname{softmax}(z_i) < 1\)

Part 2: Feedforward Neural Networks

Each layer transforms its input through weights, bias, and activation

For layer \(i\):

\[ \mathbf{x}^{[i]} = f^{[i]}\left( \mathbf{W}^{[i]} \mathbf{x}^{[i-1]} + \mathbf{b}^{[i]} \right) \]

- \(\mathbf{W}^{[i]}\): learnable weight matrix

- \(\mathbf{b}^{[i]}\): learnable bias vector

- \(f^{[i]}\): activation function

Activation functions serve different purposes in different layers

| Location | Common Choice | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Hidden layers | ReLU, GELU | Introduce nonlinearity, sparse activation |

| Binary output | Sigmoid | Probability in [0,1] |

| Multi-class output | Softmax | Probability distribution |

| Regression output | None (linear) | Unbounded real values |

The universal approximation theorem guarantees theoretical expressivity

Theorem: A feedforward network with one hidden layer and sufficient neurons can approximate any continuous function on a compact domain to arbitrary precision.

\[ \forall \epsilon > 0, \exists \hat{f}: \sup_{x \in K} |f(x) - \hat{f}(x)| < \epsilon \]

But this doesn’t mean shallow networks are always practical:

- May require exponentially many neurons

- Says nothing about learnability or generalization

Depth enables efficient representation of compositional structure

- Telgarsky (2016): Some functions require exponentially more units in shallow vs. deep networks

- Depth captures hierarchical/compositional structure naturally

- Language has recursive, hierarchical structure → depth helps

Part 3: Learning and Training Algorithms

Supervised learning optimizes parameters using labeled examples

- Training data: pairs \((\mathbf{x}, y)\) of inputs and target outputs

- Model predicts: \(\hat{y} = f_\theta(\mathbf{x})\)

- Objective: minimize average loss over training set

\[ \mathcal{L}(\theta) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \ell\big(f_\theta(\mathbf{x}_i), y_i\big) \]

Loss functions measure prediction quality

Cross-entropy loss for classification:

\[ \ell_{\text{CE}}(\hat{\mathbf{y}}, \mathbf{y}) = -\sum_{k=1}^K y_k \log \hat{y}_k \]

NLP applications of supervised learning span many tasks

| Task | Input \(\mathbf{x}\) | Output \(y\) |

|---|---|---|

| POS tagging | Word + context | POS tag (noun, verb, etc.) |

| Sentiment | Sentence/document | Sentiment class |

| NER | Word + context | Entity type or O |

| Text classification | Document | Topic/category |

Backpropagation computes gradients efficiently via the chain rule

- We need \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial W^{[l]}}\) for each layer to update weights

- Backprop propagates error signals backward through the network

\[ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W^{[l]}} = \delta^{[l]} (a^{[l-1]})^T \]

where \(\delta^{[l]} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial z^{[l]}}\) is the error signal at layer \(l\).

Error signals propagate backward through the network

The recursive error signal computation:

\[ \delta^{[l]} = \left( W^{[l+1]}\right)^T \delta^{[l+1]} \odot \sigma' (z^{[l]}) \]

Gradients drive parameter updates via gradient descent

Weight update rule:

\[ W^{[l]} \leftarrow W^{[l]} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial W^{[l]}} \]

\[ b^{[l]} \leftarrow b^{[l]} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial b^{[l]}} \]

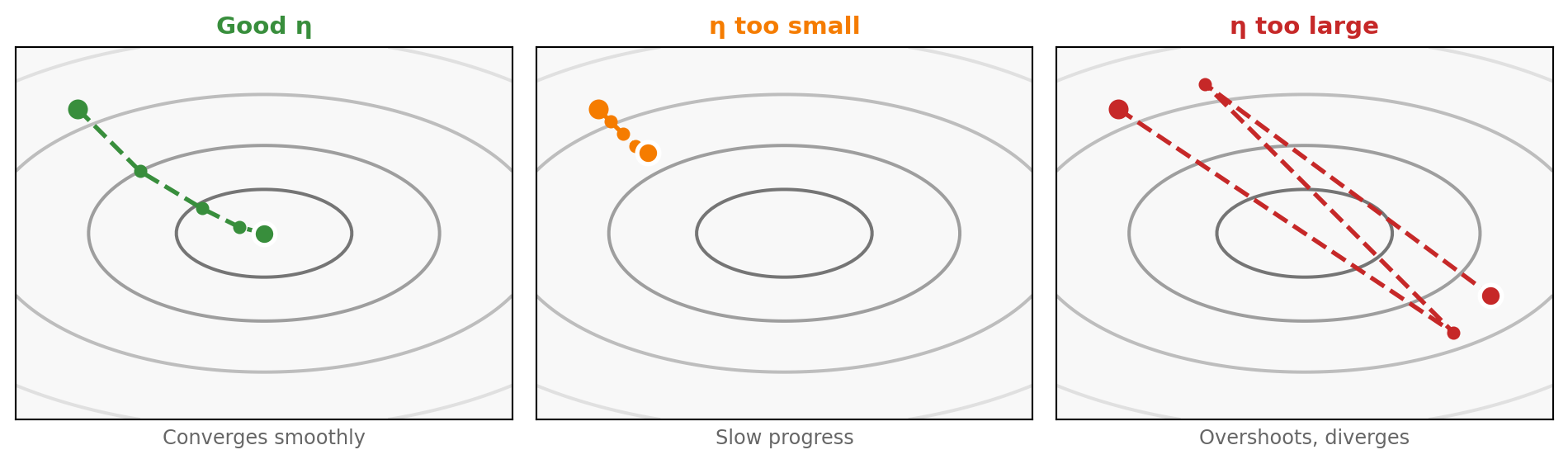

- \(\eta\): learning rate (critical hyperparameter)

- Too high → unstable, may diverge; Too low → slow convergence

Gradient descent navigates the loss landscape

Gradient descent follows the steepest downhill direction; step size η determines how far we move each update.

Backpropagation is not an optimizer—it computes gradients for optimizers

Common misconception: Backprop = training algorithm

Reality:

- Backprop: efficient gradient computation method

- SGD/Adam/etc.: optimization algorithms that use gradients

- Together they enable training, but they’re distinct concepts

(SGD, Adam)

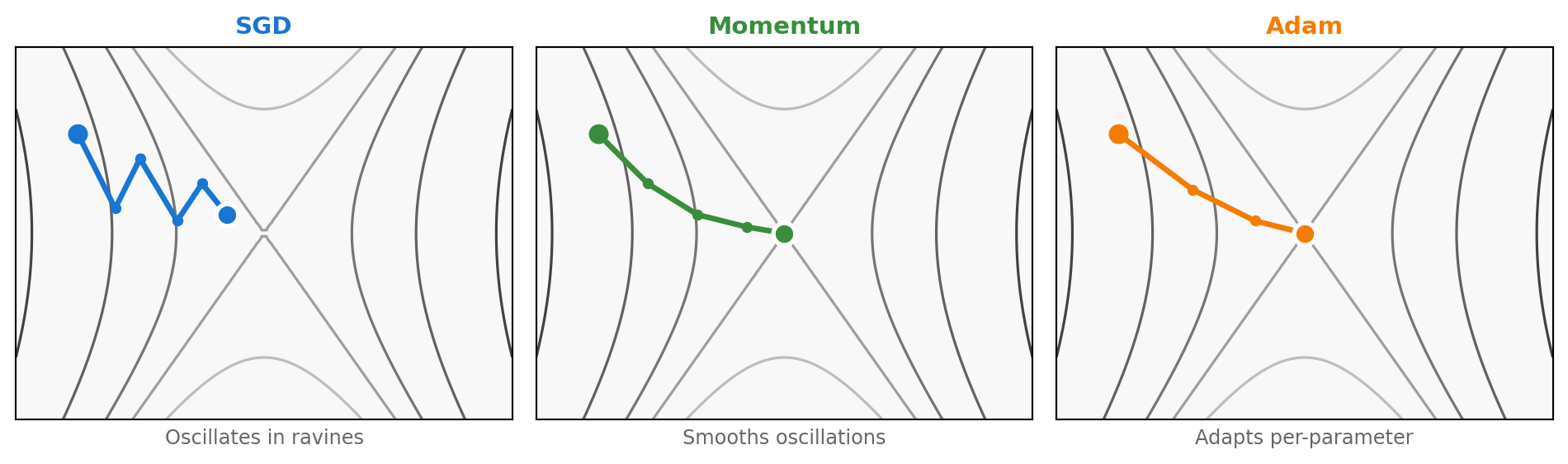

SGD processes mini-batches for efficient, noisy updates

Stochastic Gradient Descent:

\[ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \eta \nabla_\theta L(\theta_t; \mathcal{B}_t) \]

- \(\mathcal{B}_t\): random mini-batch at step \(t\)

- Noisy gradients can help escape local minima

- Much faster than full-batch gradient descent

Adam combines momentum and adaptive learning rates

Adam update equations:

\[ m_t = \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) \nabla_\theta L(\theta_t) \]

\[ v_t = \beta_2 v_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_2) (\nabla_\theta L(\theta_t))^2 \]

\[ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \eta \frac{m_t}{\sqrt{v_t} + \epsilon} \]

- \(m_t\): momentum (smoothed gradient)

- \(v_t\): adaptive scaling (per-parameter)

- Default: \(\beta_1=0.9\), \(\beta_2=0.999\), \(\epsilon=10^{-8}\)

Optimizers behave differently on complex loss surfaces

Adam combines momentum’s smoothing with per-parameter learning rate scaling—faster and more robust convergence.

Regularization prevents overfitting by constraining model capacity

Dropout forces the network to learn redundant representations

- During training: randomly set fraction \(p\) of activations to 0

- During inference: use all neurons, scale by \((1-p)\)

- Effect: no single neuron can become too important

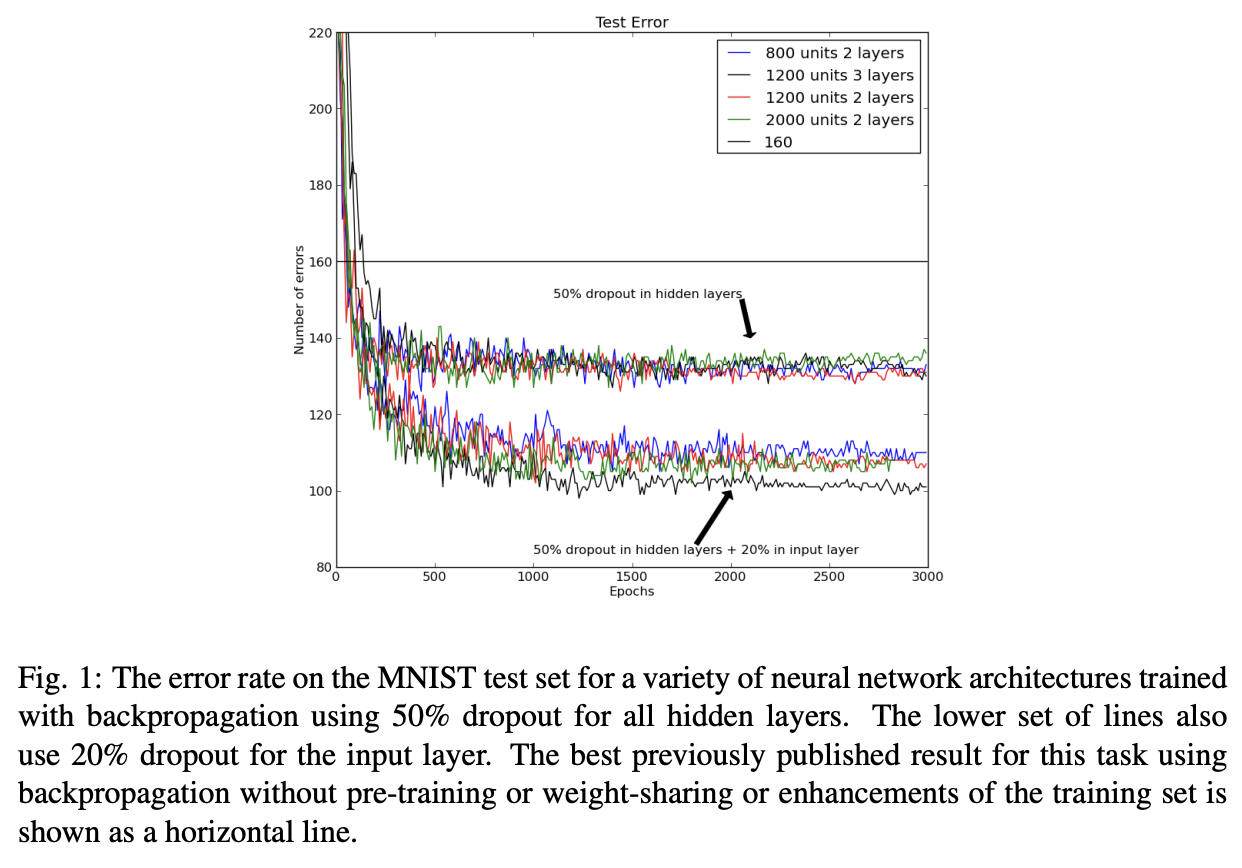

Dropout signficantly reduces overfitting

Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors (Hinton et al., 2012)

Part 4: Advanced Architectures and Extensions

Vanishing gradients make training deep networks difficult

- Gradients shrink exponentially when propagated through many layers

- For sigmoid: \(\sigma'(z) \leq 0.25\), so gradient decays by at least 4× per layer

\[ \delta^{[l]} = (W^{[l+1]})^T \delta^{[l+1]} \odot \sigma'(z^{[l]}) \]

- With 10 layers: gradient shrinks by \(\approx 4^{10} \approx 10^6\)

Exploding gradients cause training instability

- The opposite problem: gradients grow exponentially

- Occurs when \(\|W^{[l]}\| > 1\) and compounds across layers

- Symptoms: NaN losses, weights becoming infinite

Solutions:

- Gradient clipping: \(g \leftarrow g \cdot \frac{\tau}{\|g\|}\) if \(\|g\| > \tau\)

- Careful weight initialization

- Batch normalization

Proper initialization maintains gradient flow

Xavier/Glorot initialization:

\[ \text{Var}[W_{ij}] = \frac{2}{n_{in} + n_{out}} \]

He initialization (for ReLU):

\[ \text{Var}[W_{ij}] = \frac{2}{n_{in}} \]

- Goal: keep activation and gradient variance stable across layers

- Critical for training networks with 10+ layers

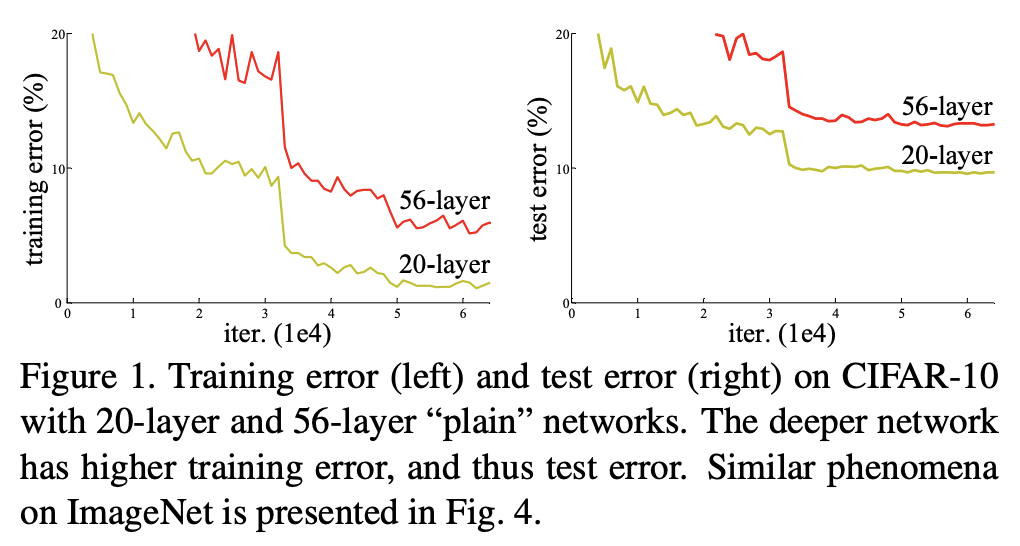

Residual connections enable training of very deep networks

- Key idea: Add input directly to output via “skip connection”

\[ \mathbf{h}^{[l+1]} = f(\mathbf{h}^{[l]}) + \mathbf{h}^{[l]} \]

Why it helps: Gradient flows directly through the skip connection:

\[ \frac{\partial \mathbf{h}^{[l+1]}}{\partial \mathbf{h}^{[l]}} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{h}^{[l]}} + \mathbf{I} \]

Residual connections: empirical evidence

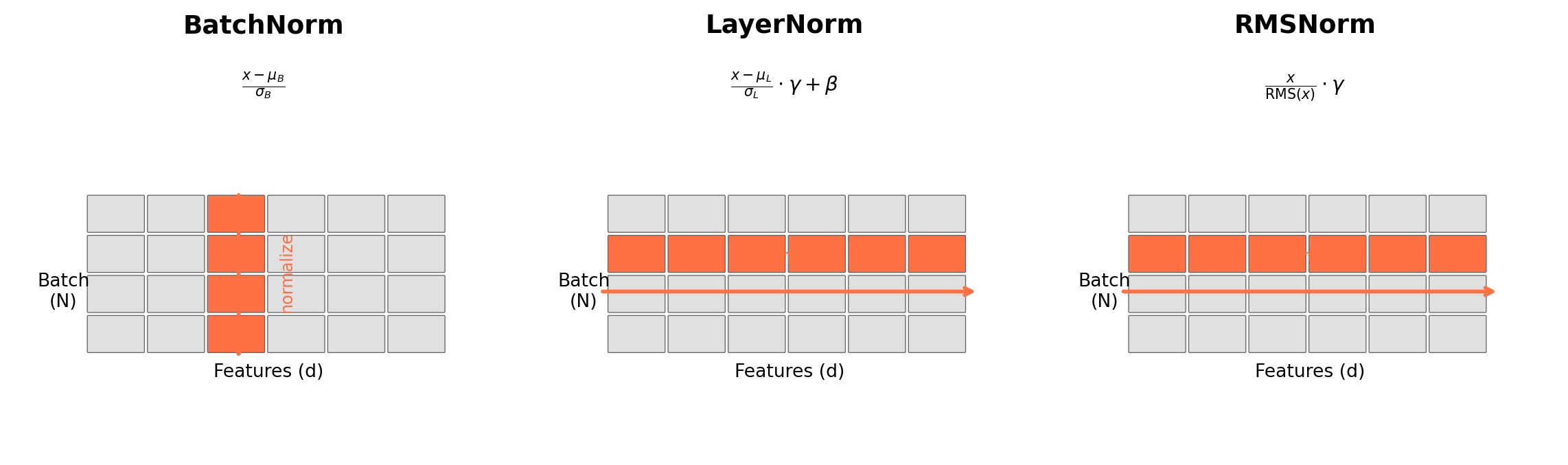

Layer normalization stabilizes training of deep networks

\[ \text{LayerNorm}(\mathbf{x}) = \gamma \odot \frac{\mathbf{x} - \mu}{\sigma + \epsilon} + \beta \]

- \(\mu, \sigma\): mean and std computed across features (per example)

- \(\gamma, \beta\): learnable scale and shift parameters

• Different behavior train vs test

• Problematic for variable-length sequences

• Same behavior train and test

• Works with any sequence length ✓

Comparing normalization techniques: BatchNorm vs LayerNorm vs RMSNorm

| BatchNorm | LayerNorm | RMSNorm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalizes | Batch dim | Feature dim | Feature dim |

| Train/Test | Different | Same | Same |

| Used in | CNNs | Transformers | LLaMA, Gemma |

RNNs model sequences by maintaining state across time steps

\[ \mathbf{h}_t = f(\mathbf{W}_{xh} \mathbf{x}_t + \mathbf{W}_{hh} \mathbf{h}_{t-1} + \mathbf{b}_h) \]

- Hidden state \(\mathbf{h}_t\) encodes information from \(x_1, \ldots, x_t\)

- Same parameters (\(\mathbf{W}_{xh}, \mathbf{W}_{hh}\)) used at every time step

The RNN sequential bottleneck limits parallelization

- \(\mathbf{h}_t\) depends on \(\mathbf{h}_{t-1}\) creates a dependency chain

- Cannot compute \(\mathbf{h}_5\) until \(\mathbf{h}_1, \mathbf{h}_2, \mathbf{h}_3, \mathbf{h}_4\) are finished

Implications:

- Cannot fully utilize parallel hardware (GPUs have thousands of cores)

- Training time scales linearly with sequence length

- Key question: What if we could process all tokens at once?

Autoregressive vs bidirectional processing

Autoregressive (left-to-right): Each position only sees the past

\[ P(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n) = \prod_{t=1}^{n} P(x_t | x_1, \ldots, x_{t-1}) \]

Bidirectional: Each position sees the entire sequence

Standard RNNs struggle with long-range dependencies

- Gradient signal degrades over long distances

- LSTM and GRU use gating mechanisms to preserve information

- Transformers use attention to directly connect distant positions

Context as a weighted combination of representations

- What if we could directly access all previous representations?

- Key insight: compute a weighted sum based on relevance

\[ \text{output}_t = \sum_{j=1}^{t} \alpha_{tj} \cdot \mathbf{v}_j \]

- \(\alpha_{tj}\): attention weight (how relevant is position \(j\) to position \(t\)?)

- \(\mathbf{v}_j\): value vector at position \(j\)

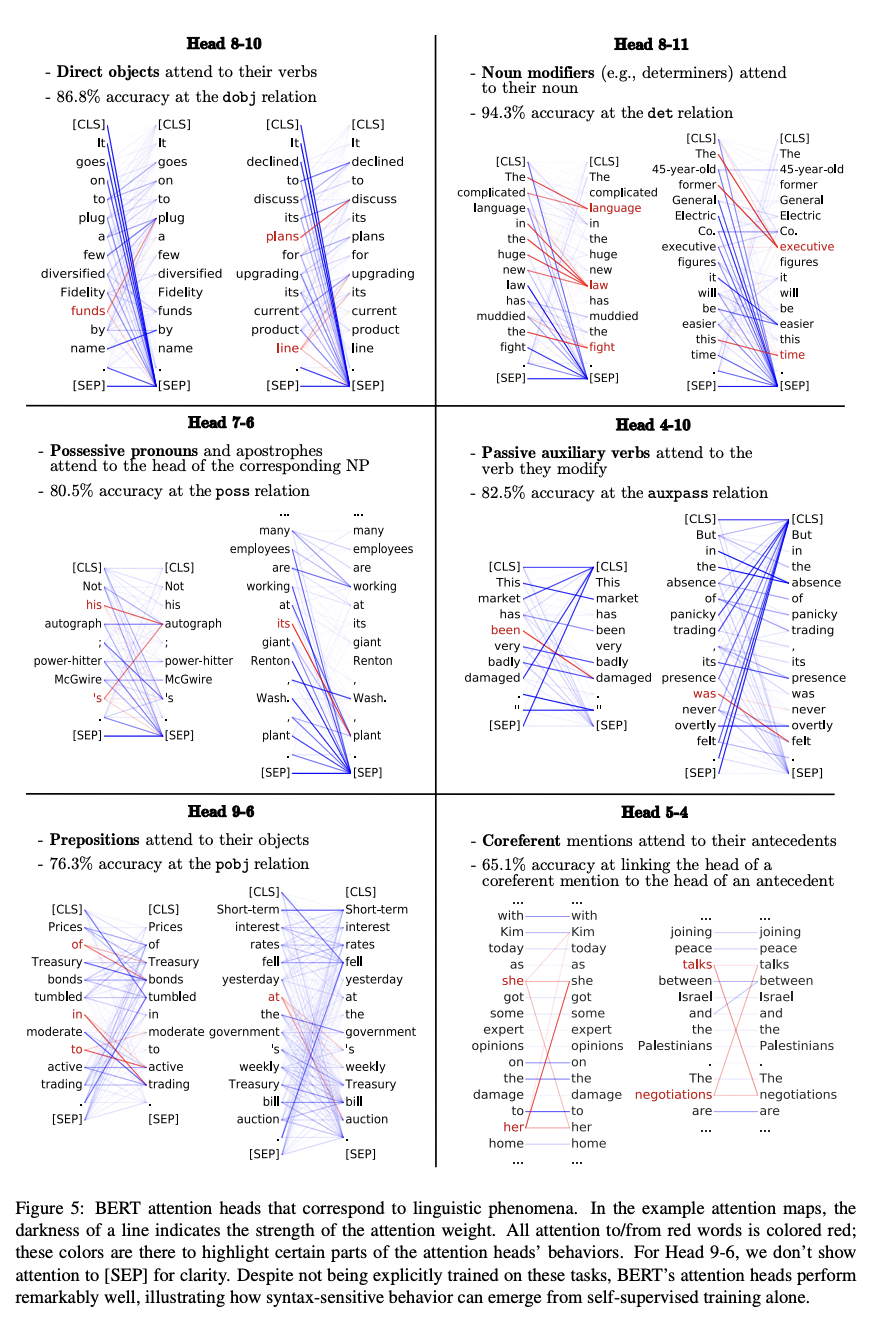

Attention weights reveal what the model focuses on

BERT attention learns coreference resolution

Position information must be explicitly encoded

- Without recurrence, order information is lost

- “Dog bit man” and “man bit dog” would be identical!

Key question: How do we inject position information into parallel architectures?

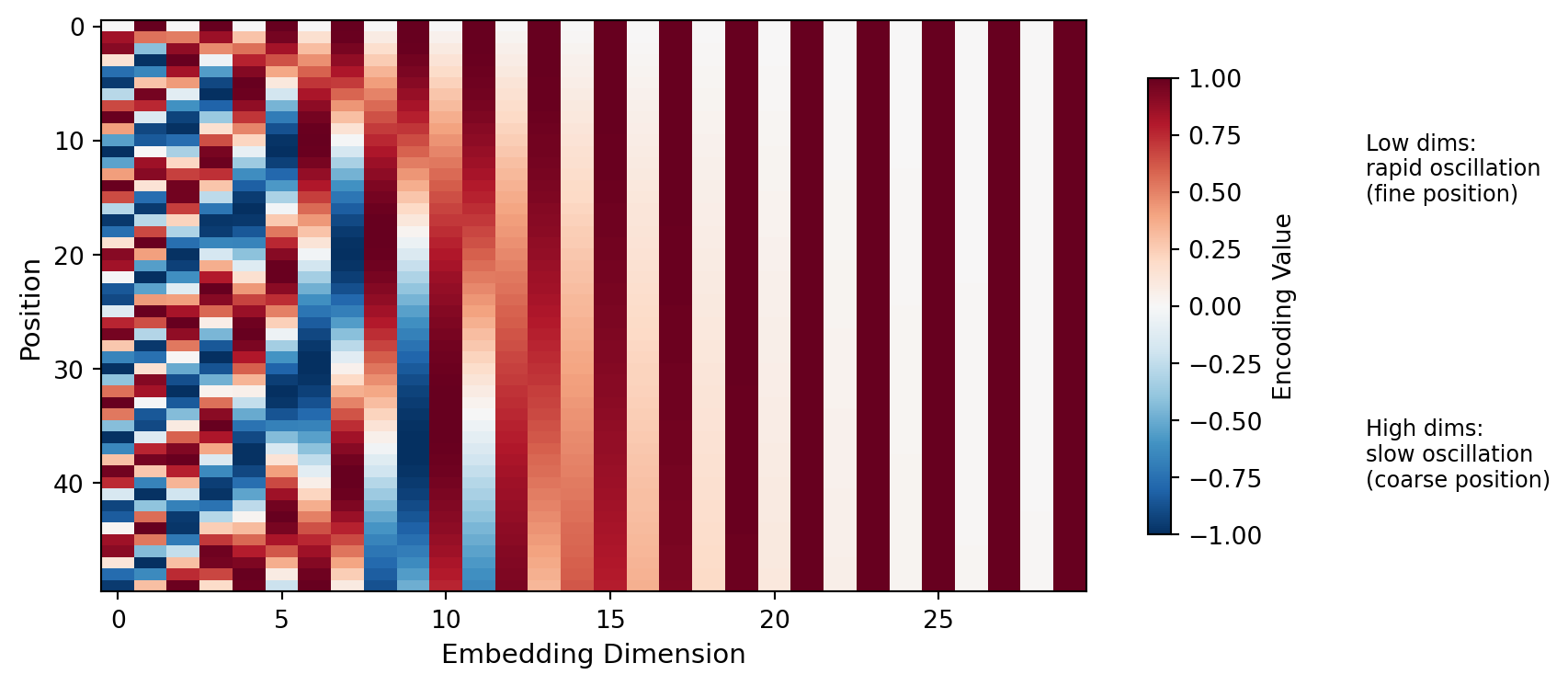

Sinusoidal position encodings (Vaswani et al., 2017)

Add a position-dependent vector to each token embedding:

\[ PE_{(pos, 2i)} = \sin\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{2i/d}}\right) \quad PE_{(pos, 2i+1)} = \cos\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{2i/d}}\right) \]

Key properties: Each position gets a unique encoding; relative positions computable via linear transformation; generalizes to longer sequences.

Part 5: Applications

Neural networks power core NLP tasks

| Task | Architecture | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Text classification | Feedforward / CNN / Transformer | Class probabilities (softmax) |

| Language modeling | RNN / Transformer | Next token probabilities |

| Sequence labeling | BiLSTM / Transformer | Tag per token |

| Machine translation | Encoder-decoder | Target sequence |

Text classification assigns labels to documents

'Great movie!'

Layer

(CNN/LSTM/Transformer)

P(neg)=0.08

Applications: Sentiment analysis, spam detection, topic classification

Language modeling predicts the next token in a sequence

\[ P(w_t | w_1, \ldots, w_{t-1}) = \text{softmax}(\mathbf{W} \mathbf{h}_{t-1} + \mathbf{b}) \]

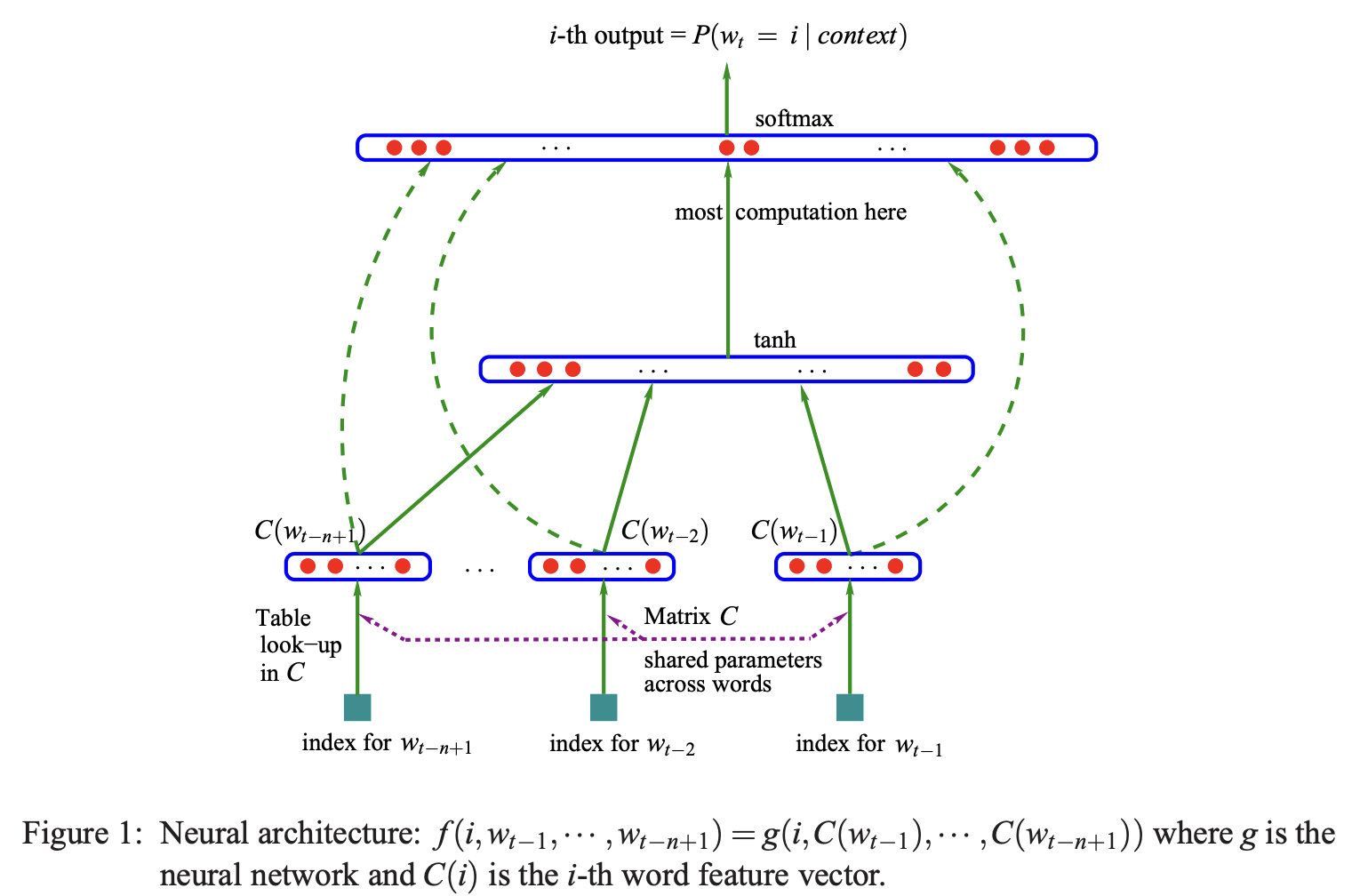

Bengio et al. (2003) neural language model: word embeddings → hidden layer → softmax over vocabulary

Neural networks excel across diverse domains

- Same fundamental principles (backprop, gradient descent) apply

- Architecture choices encode domain-specific inductive biases

Part 6: Further Reading and Historical Notes

Key references for deeper understanding

Textbooks:

- Goodfellow, Bengio, & Courville (2016), Deep Learning — comprehensive theory and practice

- Jurafsky & Martin, Speech and Language Processing Ch. 6-8

Key milestones in neural network history

Summary: Neural Networks - Key Takeaways

- Architecture: Networks of neurons organized in layers; feedforward vs. recurrent

- Learning: Supervised learning minimizes loss via gradient descent

- Backpropagation: Efficient gradient computation using the chain rule

- Optimization: SGD, Adam; regularization (dropout, L2) prevents overfitting

- Challenges: Vanishing/exploding gradients addressed by careful design

- Applications: Text classification, language modeling, and beyond

Questions?

Coming up next: Transformers and attention mechanisms

Resources:

- Goodfellow et al. Deep Learning (free online)

- 3Blue1Brown neural network videos (visual intuition)

- PyTorch tutorials (hands-on practice)