%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'lineColor': '#2f2f2f', 'textColor': '#111111', 'primaryBorderColor': '#2f2f2f', 'fontSize': '18px'}}}%%

flowchart LR

X["$$x = [x_1, x_2, x_3]$$"]

W["$$w = [w_1, w_2, w_3]$$"]

B["$$b$$"]

Z["$$z = w^\\top x + b$$"]

S["$$\\hat{y} = \\sigma(z)$$"]

P["$$P(y=1\\mid x)=\\hat{y}$$"]

X --> Z

W --> Z

B --> Z

Z --> S --> P

classDef input fill:#e9f2ff,stroke:#1f4e79,stroke-width:1.2px,color:#0b1f33;

classDef compute fill:#f3f7ff,stroke:#1f4e79,stroke-width:1.2px,color:#0b1f33;

classDef output fill:#fff1e6,stroke:#8a3b12,stroke-width:1.2px,color:#3b1a06;

class X,W,B input;

class Z,S compute;

class P output;

Text Classification

2026-01-13

Administrivia

- Course website has some updates

- Noah Smith will give a guest lecture February 3rd, please attend in person!

- A1 will be released Thursday, plan ahead

Sources

Content derived from: J&M Ch. 4

Part 1: Foundations of Text Classification

Text classification assigns predefined categories to text using supervised learning. (1/5)

- Text classification assigns predefined categories to text using supervised learning.

- Let \(x\) denote an input text (e.g., document, sentence), and \(y\) a discrete label.

- The classification function \(f_\theta(x): \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \mathcal{Y}\) is learned from labeled data \(\mathcal{D} = \{(x^{(i)}, y^{(i)})\}_{i=1}^N\).

Text classification assigns predefined categories to text using supervised learning. (2/5)

- For binary labels \(y^{(i)} \in \{0,1\}\), define \(\hat{y}^{(i)} = p_\theta(y=1 \mid x^{(i)})\).

- Bernoulli likelihood: \[ p_\theta(y^{(i)} \mid x^{(i)}) = \hat{y}^{(i) y^{(i)}} (1-\hat{y}^{(i)})^{1-y^{(i)}} \]

- MLE maximizes the log-likelihood: \[ \hat{\theta}_{\mathrm{MLE}} = \arg\max_\theta \sum_{i=1}^N \log p_\theta(y^{(i)} \mid x^{(i)}) \]

Text classification assigns predefined categories to text using supervised learning. (3/5)

- Negative log-likelihood gives cross-entropy: \[ \mathcal{L}(\theta) = -\sum_{i=1}^N \left[y^{(i)} \log \hat{y}^{(i)} + (1-y^{(i)}) \log(1-\hat{y}^{(i)})\right] \]

- Empirical risk is the average loss: \[ \hat{\theta} = \arg\min_\theta \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \mathcal{L}^{(i)} = \arg\min_\theta \hat{R}_n (\theta) \]

- Multiclass generalization uses softmax cross-entropy (\(-\log \hat{y}_{y}\)).

Text classification assigns predefined categories to text using supervised learning. (4/5)

- Tasks include binary, multiclass, and multilabel classification (e.g., spam detection, sentiment analysis).

- Binary: \(\mathcal{Y} = \{0, 1\}\) (e.g., spam vs. not spam)

- Multiclass: \(\mathcal{Y} = \{1, \dots, K\}\) (e.g., topic labeling with \(K\) classes)

- Multilabel: \(\mathcal{Y} \subseteq \{1, \dots, K\}\) (e.g., documents tagged with multiple topics)

- The choice impacts the loss function: sigmoid for binary, softmax for multiclass, sigmoid per label for multilabel.

Binary, multiclass, multilabel: outputs and loss

Binary

Email → Spam?

0/1- Output: \(\hat{y} = \sigma(z)\)

- Loss: \(-\big[y\log \hat{y} + (1-y)\log(1-\hat{y})\big]\)

Multiclass

Doc → Topic

{1..K}- Output: \(\hat{y}_k = \mathrm{softmax}(z)_k\)

- Loss: \(-\log \hat{y}_{y}\)

Multilabel

Doc → Tags

{0,1}^K- Output: \(\hat{y}_k = \sigma(z_k)\)

- Loss: \(-\sum_k \big[y_k\log \hat{y}_k + (1-y_k)\log(1-\hat{y}_k)\big]\)

Text classification assigns predefined categories to text using supervised learning. (5/5)

- Clear problem formulation enables effective model selection and evaluation in NLP applications.

- Precise definition of input/output space (\(\mathcal{X}, \mathcal{Y}\)) guides feature engineering and architecture.

- Evaluation metrics (accuracy, F1, AUC) depend on task structure.

- Spam filtering (binary)

- Sentiment analysis (binary/multiclass)

- News categorization (multiclass)

- Multi-topic assignment (multilabel)

Text data is represented as feature vectors using models like Bag-of-Words and TF/IDF. (1/3)

Text data is represented as feature vectors using models like Bag-of-Words and TF/IDF.

Bag-of-Words (BoW) encodes a document as a sparse vector of term counts.

- Given vocabulary \(V = \{w_1, ..., w_{|V|}\}\), a document \(d\) is represented as

\[ \mathbf{x}_d = [c(w_1, d), c(w_2, d), ..., c(w_{|V|}, d)] \]

where \(c(w_i, d)\) is the count of word \(w_i\) in \(d\).

- Ignores word order, capturing only term presence and frequency.

Toy Bag-of-Words example

- Corpus sentence:

- “The quick brown fox jumped over the quick, lazy sheep dog.”

- Lowercase + split into tokens, then count each word.

| Word | Count |

|---|---|

| the | 2 |

| quick | 2 |

| brown | 1 |

| fox | 1 |

| jumped | 1 |

| over | 1 |

| lazy | 1 |

| sheep | 1 |

| dog | 1 |

- Encode a new sentence with the same vocabulary:

- “The quick orange fox, jumped over the lazy, slow turtle.”

- Vocabulary order: the, quick, brown, fox, jumped, over, lazy, sheep, dog

- Encoded vector: [2, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0]

- Out-of-vocabulary words are ignored: orange, slow, turtle

Text data is represented as feature vectors using models like Bag-of-Words and TF/IDF. (2/3)

- Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF/IDF) re-weights terms to emphasize discriminative words.

- For term \(t\) in document \(d\):

\[ \mathrm{tfidf}(t, d) = \mathrm{tf}(t, d) \cdot \mathrm{idf}(t) \]

where \(\mathrm{tf}(t, d) = \frac{c(t, d)}{\sum_{t'} c(t', d)}\) and \(\mathrm{idf}(t) = \log \frac{N}{n_t}\) with \(N\) total documents and \(n_t\) documents containing \(t\).

Toy TF/IDF example with 3 documents

Documents:

- \(d_1\): “apple banana apple”

- \(d_2\): “banana carrot”

- \(d_3\): “apple carrot carrot”

Vocabulary: \(\{\text{apple}, \text{banana}, \text{carrot}\}\), \(N=3\).

Document frequencies: \(n_{\text{apple}}=2\), \(n_{\text{banana}}=2\), \(n_{\text{carrot}}=2\).

So \(\mathrm{idf}(\cdot)=\log \frac{3}{2}\) for all three terms.

Example TF/IDF:

- For term “apple” in \(d_1\): \(\mathrm{tf}=\frac{2}{3}\), so \(\mathrm{tfidf}=\frac{2}{3}\log\frac{3}{2}\).

- For term “carrot” in \(d_2\): \(\mathrm{tf}=\frac{1}{2}\), so \(\mathrm{tfidf}=\frac{1}{2}\log\frac{3}{2}\).

From TF/IDF to feature vectors

Fix vocabulary order: \(\big[\text{apple},\ \text{banana},\ \text{carrot}\big]\).

TF vectors:

- \(d_1\): \(\big[\frac{2}{3},\ \frac{1}{3},\ 0\big]\)

- \(d_2\): \(\big[0,\ \frac{1}{2},\ \frac{1}{2}\big]\)

- \(d_3\): \(\big[\frac{1}{3},\ 0,\ \frac{2}{3}\big]\)

Since \(\mathrm{idf}=\log\frac{3}{2}\) for every term, TF/IDF feature vectors are:

- \(v_1=\big[\frac{2}{3}\log\frac{3}{2},\ \frac{1}{3}\log\frac{3}{2},\ 0\big]\)

- \(v_2=\big[0,\ \frac{1}{2}\log\frac{3}{2},\ \frac{1}{2}\log\frac{3}{2}\big]\)

- \(v_3=\big[\frac{1}{3}\log\frac{3}{2},\ 0,\ \frac{2}{3}\log\frac{3}{2}\big]\)

These vectors are the rows of the TF/IDF feature matrix for the corpus.

Text data is represented as feature vectors using models like Bag-of-Words and TF/IDF. (3/3)

- Applications of TF/IDF:

- Enables use of linear models (e.g., logistic regression, SVMs) for text classification.

- Forms the basis for feature selection and further dimensionality reduction.

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance. (1/8)

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance.

Accuracy quantifies overall correctness:

\[ \text{Accuracy} = \frac{TP + TN}{TP + FP + TN + FN} \]

where \(TP\) = true positives, \(TN\) = true negatives, \(FP\) = false positives, \(FN\) = false negatives.

Spam dataset: Is this a good model?

- Suppose 1,000,000 emails: 999,000 ham (99.9%) and 1,000 spam (0.1%).

- A model predicts ham for every message.

- Accuracy = 999,000 / 1,000,000 = 99.9%.

- Is this a good model?

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance. (2/8)

- Precision and recall are class-specific:

\[ \text{Precision} = \frac{TP}{TP + FP} \qquad \text{Recall} = \frac{TP}{TP + FN} \]

- Precision: proportion of predicted positives that are correct.

- Recall: proportion of actual positives that are retrieved.

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance. (3/8)

- F1-score balances precision and recall:

\[ F_1 = 2 \cdot \frac{\text{Precision} \cdot \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}} \]

- Generalizes to \(F_\beta\) for weighting recall vs. precision.

Note

\(F_\beta\) formula: \[ F_\beta = (1 + \beta^2) \cdot \frac{\text{Precision} \cdot \text{Recall}}{(\beta^2 \cdot \text{Precision}) + \text{Recall}} \]

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance. (4/8)

The confusion matrix summarizes true/false positives/negatives; F1 balances precision and recall.

The confusion matrix structure:

\[ \begin{array}{c|cc} & \text{Predicted } + & \text{Predicted } - \\ \hline \text{Actual } + & TP & FN \\ \text{Actual } - & FP & TN \\ \end{array} \]

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance. (5/8)

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance. (6/8)

- Directly visualizes classifier errors and successes.

- Precision-Recall tradeoff:

- High precision, low recall: conservative classifier.

- High recall, low precision: aggressive classifier.

- \(F_1\)-score is harmonic mean, punishing extreme imbalance between precision and recall.

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance. (7/8)

Choosing the right metric is crucial, especially for imbalanced data and model comparison.

When would you tolerate more false positives to catch almost every true case (prioritize recall)?

When would you tolerate more misses to avoid false alarms (prioritize precision)?

Evaluation metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score measure classifier performance. (8/8)

- Accuracy can be misleading for imbalanced classes (e.g., rare disease detection).

- Example: 99% accuracy if classifier always predicts majority class.

- For skewed data, prefer precision, recall, or \(F_\beta\) tailored to application risk.

- E.g., spam detection: high recall, moderate precision.

- Cross-validation strategies (e.g., stratified \(k\)-fold) provide robust estimates and control for class imbalance during evaluation.

Picking \(F_\beta\): example scenarios

- Choose \(F_{\beta=2}\) when recall matters more than precision (misses are costly).

- Example: cancer screening triage; missing a true case is worse than a false alarm.

- Example: safety incident detection; you want to catch nearly all real incidents.

- Choose \(F_{\beta=1/2}\) when precision matters more than recall (false alarms are costly).

- Example: automated legal holds; false positives are expensive to review.

- Example: account freeze alerts; avoid disrupting legitimate users.

Part 2: Logistic Regression

Discriminative models directly model P(y|x), focusing on decision boundaries between classes. (1/4)

- Discriminative models directly estimate conditional probability \(P(y|x)\), emphasizing decision boundaries.

- The model focuses on learning the mapping from features \(x\) to labels \(y\), rather than modeling \(P(x)\) or \(P(x, y)\).

- Contrasts with generative models, which require explicit modeling of the joint distribution \(P(x, y)\) or the marginal \(P(x)\).

- Inductive bias is centered on maximizing separation between classes in feature space.

Discriminative models directly model P(y|x), focusing on decision boundaries between classes. (2/4)

- Logistic regression leverages feature vectors \(x\) and weight parameters \(w\) to model \(P(y=1|x)\) via the sigmoid activation.

- The model computes:

\[ P(y=1|x) = \sigma(w \cdot x + b) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(w \cdot x + b)}} \]

Logistic regression computes a weighted sum (logit) and applies a sigmoid.

Discriminative models directly model P(y|x), focusing on decision boundaries between classes. (3/4)

- Training involves optimizing weights \(w\) and bias \(b\) to minimize the cross-entropy loss:

\[ \mathcal{L}(w, b) = -[y \log \hat{y} + (1 - y) \log(1 - \hat{y})] \]

- The decision boundary is the hyperplane \(w \cdot x + b = 0\), learned directly from labeled data.

Logistic loss is the negative log-likelihood of a Bernoulli model. (1/1)

- Assume \(y^{(i)} \in \{0,1\}\) with Bernoulli likelihood:

\[ p_\theta(y^{(i)} \mid x^{(i)}) = \hat{y}^{(i) y^{(i)}} (1-\hat{y}^{(i)})^{1-y^{(i)}}, \quad \hat{y}^{(i)}=\sigma(w^\top x^{(i)}+b) \]

- MLE maximizes \(\prod_i p_\theta(y^{(i)} \mid x^{(i)})\), equivalently minimizes negative log-likelihood:

\[ -\sum_{i=1}^N \log p_\theta(y^{(i)} \mid x^{(i)}) = -\sum_{i=1}^N \left[y^{(i)} \log \hat{y}^{(i)} + (1-y^{(i)}) \log(1-\hat{y}^{(i)})\right] \]

- This is exactly the binary cross-entropy (logistic) loss.

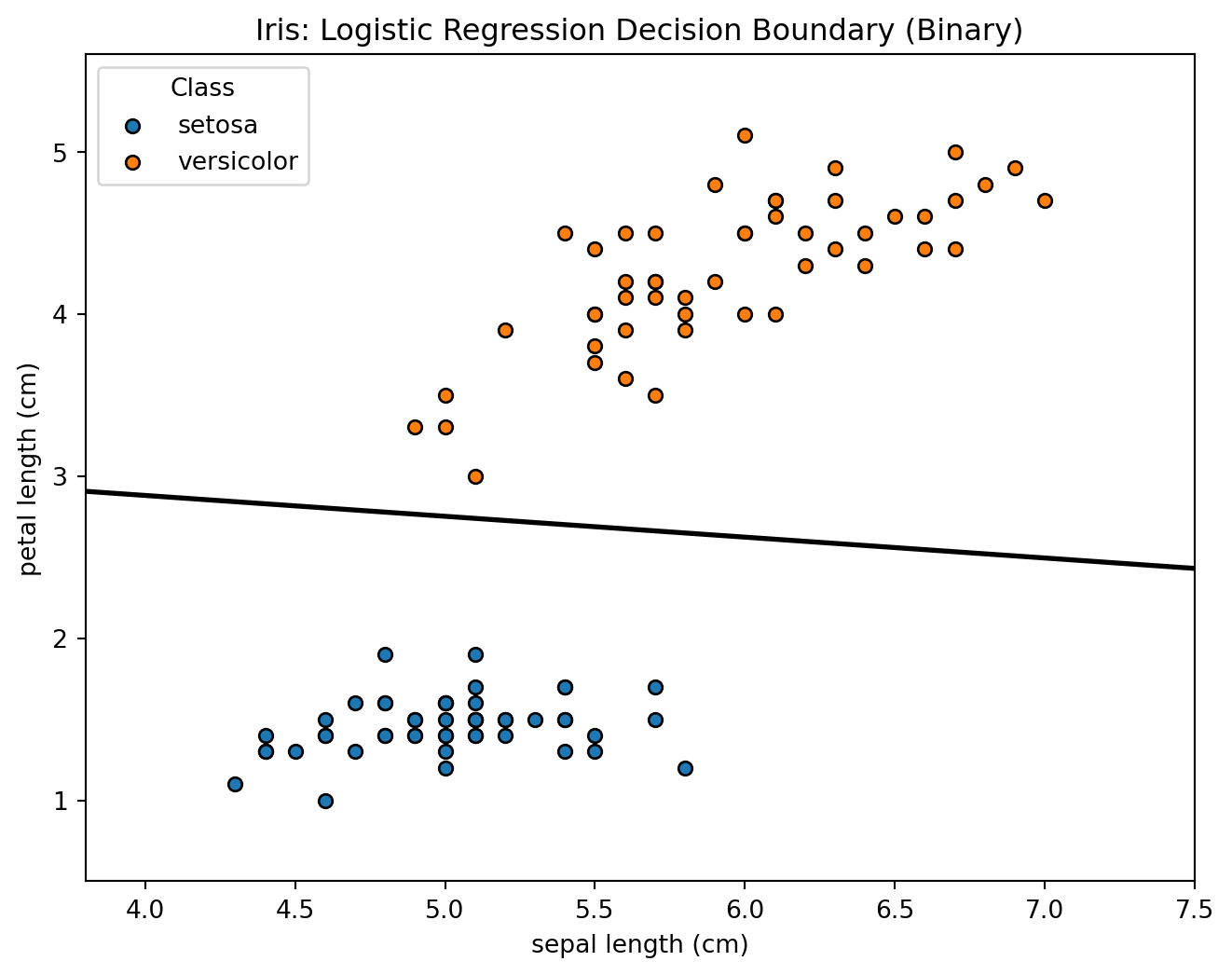

Iris dataset: binary classification

Classic Iris measurements (sepal/petal lengths) with logistic regression classifying setosa vs. versicolor using a 2D decision boundary.

Discriminative models directly model P(y|x), focusing on decision boundaries between classes. (4/4)

- Discriminative approaches enable robust text classification by allowing targeted feature engineering and direct optimization for accuracy.

- Feature engineering can encode linguistic, lexical, or syntactic cues (e.g., word presence, n-grams, TF-IDF scores).

- Empirical performance improves as features are tailored to the structure and nuances of text data.

- Example: In sentiment classification, features such as polarity lexicon counts or phrase patterns can be incorporated to improve \(P(y|x)\) estimation.

Binary logistic regression models the probability of a binary outcome using the sigmoid function. (1/7)

Binary logistic regression models the probability of a binary outcome using the sigmoid function.

For input \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d\), the model defines the probability of class \(y \in \{0,1\}\) as:

\[ P(y=1|\mathbf{x}; \mathbf{w}, b) = \sigma(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x} + b) \]

where \(\sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}}\) is the sigmoid activation.

Binary logistic regression models the probability of a binary outcome using the sigmoid function. (2/7)

- Intuition: The sigmoid maps real-valued scores to \([0,1]\), enabling probabilistic interpretation for binary classification.

Applications:

Text sentiment classification (positive/negative)

Spam detection (spam/not spam)

Medical diagnosis (disease/no disease)

Binary logistic regression models the probability of a binary outcome using the sigmoid function. (3/7)

The model uses cross-entropy loss and optimizes parameters via (stochastic) gradient descent.

The cross-entropy loss for a single data point is:

\[ \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{w}, b) = -y \log \hat{y} - (1-y) \log (1-\hat{y}) \]

where \(\hat{y} = \sigma(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x} + b)\).

- For dataset \(\{(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}, y^{(i)})\}_{i=1}^N\), the total loss:

\[ \mathcal{J}(\mathbf{w}, b) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \mathcal{L}^{(i)} \]

Binary logistic regression models the probability of a binary outcome using the sigmoid function. (4/7)

Gradient Descent Algorithm:

For each data point, compute the predicted probability \(\hat{y}\) using the sigmoid function.

Calculate gradients:

- \(\nabla_{\mathbf{w}} = (\hat{y} - y) \mathbf{x}\)

- \(\nabla_b = (\hat{y} - y)\)

Update parameters:

- \(\mathbf{w} \leftarrow \mathbf{w} - \eta \nabla_{\mathbf{w}}\)

- \(b \leftarrow b - \eta \nabla_b\)

Binary logistic regression models the probability of a binary outcome using the sigmoid function. (5/7)

Binary logistic regression models the probability of a binary outcome using the sigmoid function. (6/7)

Stochastic gradient descent (SGD) updates parameters using individual samples, improving convergence on large datasets.

This enables effective classification and sets the stage for regularization to prevent overfitting.

Logistic regression provides probabilistic outputs, interpretable coefficients, and a convex loss surface, facilitating robust training.

Overfitting can occur, especially with high-dimensional data; regularization (e.g., L1, L2 penalties) mitigates this by constraining parameter magnitudes.

Binary logistic regression models the probability of a binary outcome using the sigmoid function. (7/7)

Next:

- We will examine regularization strategies and their effect on generalization in logistic regression.

Regularization penalties prevent overfitting by constraining parameter magnitudes. (1/3)

- Regularization adds a penalty term to the loss function to discourage large parameter values.

- \(L_p\) norm: \(\|\mathbf{w}\|_p = \left(\sum_{j=1}^d |w_j|^p\right)^{1/p}\)

- \(L_1\) regularization (Lasso): \(\|\mathbf{w}\|_1 = \sum_{j=1}^d |w_j|\)

- \(L_2\) regularization (Ridge): \(\|\mathbf{w}\|_2^2 = \sum_{j=1}^d w_j^2\)

- Regularized loss: \[ \mathcal{J}_{\text{reg}}(\mathbf{w}, b) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \mathcal{L}^{(i)} + \lambda \|\mathbf{w}\|_p \]

where \(\lambda\) controls the regularization strength.

Regularization penalties prevent overfitting by constraining parameter magnitudes. (2/3)

- L2 regularization derives from a Gaussian prior on weights:

- Prior: \(p(\mathbf{w}) \propto \exp\left(-\frac{\lambda}{2}\|\mathbf{w}\|_2^2\right)\)

- MAP estimation adds the penalty \(\lambda \|\mathbf{w}\|_2^2\) to the loss.

- L1 regularization derives from a Laplace (double exponential) prior:

- Prior: \(p(\mathbf{w}) \propto \exp\left(-\lambda \|\mathbf{w}\|_1\right)\)

- MAP estimation adds the penalty \(\lambda \|\mathbf{w}\|_1\) to the loss.

Regularization penalties prevent overfitting by constraining parameter magnitudes. (3/3)

L1 regularization promotes sparsity by setting many weights to zero, enabling feature selection.

L2 regularization shrinks weights uniformly, improving generalization without feature selection.

Practical guidance:

- Use L2 (Ridge) for dense feature spaces or when all features may be informative.

- Use L1 (Lasso) when feature selection is desired or the feature space is sparse.

- Elastic Net combines L1 and L2 for balanced regularization.

Multiclass logistic regression can be done via one-vs-rest or softmax approaches. (1/3)

- Multiclass logistic regression can be performed using either one-vs-rest or softmax approaches.

- In the one-vs-rest (OvR) strategy, \(K\) binary classifiers are trained, one per class, each distinguishing one class from all others.

- For class \(k\), the classifier computes \(P(y = k \mid \mathbf{x}) = \sigma(\mathbf{w}_k^\top \mathbf{x} + b_k)\)

- The predicted class is \(\arg\max_k P(y = k \mid \mathbf{x})\).

- The softmax approach generalizes logistic regression to multiple classes by modeling all classes jointly.

Multiclass logistic regression can be done via one-vs-rest or softmax approaches. (2/3)

For \(K\) classes, the probability of class \(k\) is: \[ P(y = k \mid \mathbf{x}) = \frac{\exp(\mathbf{w}_k^\top \mathbf{x} + b_k)}{\sum_{j=1}^{K} \exp(\mathbf{w}_j^\top \mathbf{x} + b_j)} \]

The predicted class is again \(\arg\max_k P(y = k \mid \mathbf{x})\).

- Both approaches use the cross-entropy loss, but the softmax formulation yields a single, vector-valued gradient, while OvR involves \(K\) separate binary losses.

Multiclass logistic regression can be done via one-vs-rest or softmax approaches. (3/3)

Applications:

- Text classification with more than two categories (e.g., topic or sentiment classification).

- Part-of-speech tagging, where each word must be assigned to one of many possible tags.

Multiclass logistic regression: OvR vs. softmax (diagram)

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'lineColor': '#2f2f2f', 'textColor': '#111111', 'primaryBorderColor': '#2f2f2f', 'fontSize': '18px'}}}%%

flowchart LR

X["$$x \\in \\mathbb{R}^3$$"]

subgraph A["OvR (K=3 sigmoids)"]

direction LR

O1["$$z_k = w_k^\\top x + b_k,\\ k\\in\\{1,2,3\\}$$"] --> O2["$$\\hat{p}_k = \\sigma(z_k)$$"] --> O3["$$\\hat{y} = \\arg\\max_k \\hat{p}_k$$"]

end

subgraph B["Softmax (shared norm.)"]

direction LR

S1["$$z_k = w_k^\\top x + b_k,\\ k\\in\\{1,2,3\\}$$"] --> S2["$$\\hat{p}_k = \\dfrac{e^{z_k}}{\\sum_{j=1}^{3} e^{z_j}}$$"] --> S3["$$\\hat{y} = \\arg\\max_k \\hat{p}_k$$"]

end

X --> O1

X --> S1

classDef ovr fill:#e9f2ff,stroke:#1f4e79,stroke-width:1.2px,color:#0b1f33;

classDef soft fill:#fff1e6,stroke:#8a3b12,stroke-width:1.2px,color:#3b1a06;

class X,O1,O2,O3 ovr;

class S1,S2,S3 soft;

style A fill:#f3f7ff,stroke:#1f4e79,color:#0b1f33;

style B fill:#fff5ed,stroke:#8a3b12,color:#3b1a06;

Takeaways:

- OvR is simpler to train with binary solvers and allows per-class thresholds.

- Softmax provides a single, normalized probability distribution across classes.

Part 3: Statistical and Experimental Considerations

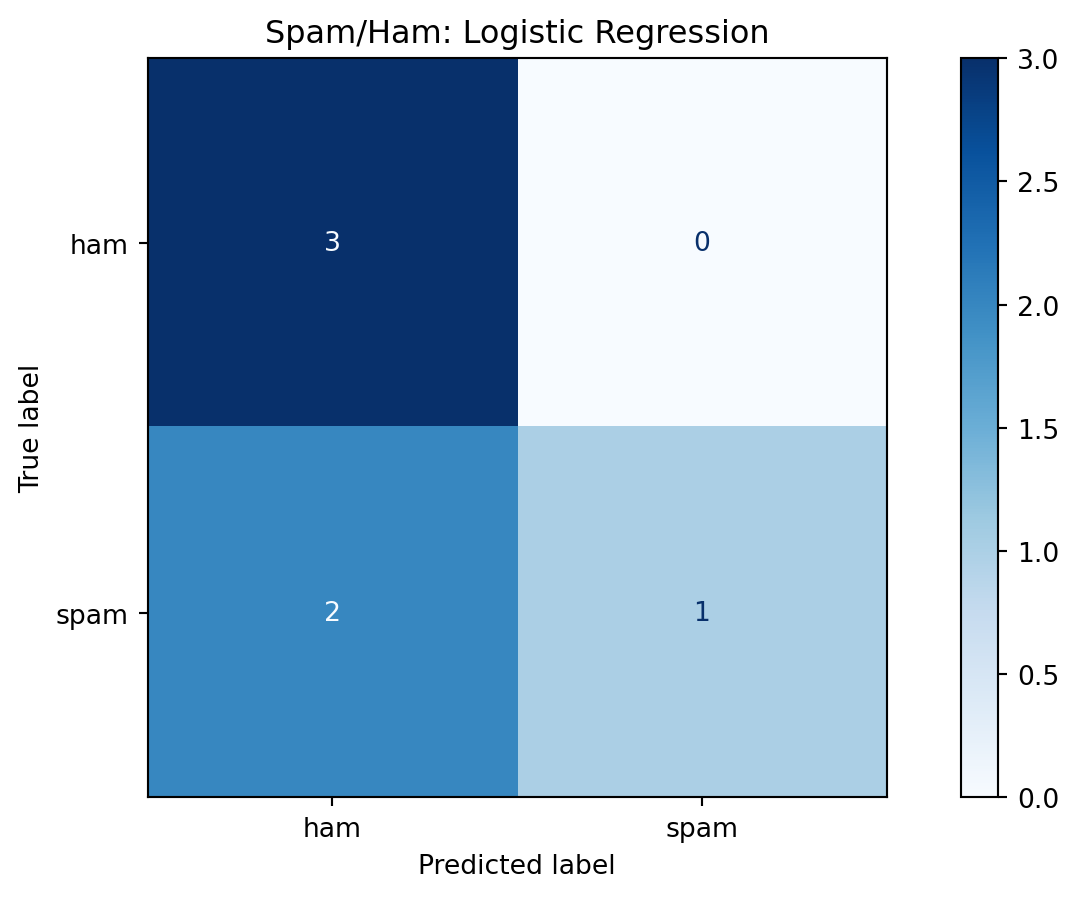

Statistical significance testing is essential for validating NLP experiment results. (1/8)

- Example: Trained logistic regression on a toy spam/ham dataset.

- We evaluate predictions with a confusion matrix before running significance tests.

Statistical significance testing is essential for validating NLP experiment results. (2/8)

- Statistical hypothesis testing quantifies whether observed performance differences are likely due to chance.

- Null hypothesis \(H_0\): No difference between systems’ true performance.

- \(p\)-value: Probability of observing results at least as extreme as those measured, assuming \(H_0\) is true.

Statistical significance testing is essential for validating NLP experiment results. (3/8)

- In NLP, model evaluation metrics (e.g., accuracy, F1) are subject to sampling noise.

- Random train/test splits and annotation errors introduce variance.

- Without significance testing, small metric improvements may be spurious.

- Example:

- Comparing two classifiers with 80.2% vs. 80.7% accuracy on a test set of size \(N\).

- Is the 0.5% difference meaningful, or within random variation?

Statistical significance testing is essential for validating NLP experiment results. (4/8)

Methods like bootstrap confidence intervals and tests across datasets assess result reliability.

- The bootstrap estimates confidence intervals by repeatedly resampling the test set:

\[ \text{For } b = 1, \dots, B: \quad \text{Sample with replacement to create set } D_b \]

\[ \text{Compute metric: } \theta^{(b)} = \text{Metric}(D_b) \]

\[ \text{Form empirical distribution: } \{\theta^{(1)}, \dots, \theta^{(B)}\} \]

Statistical significance testing is essential for validating NLP experiment results. (5/8)

Statistical significance testing is essential for validating NLP experiment results. (6/8)

- Significance testing across datasets (e.g., paired \(t\)-test, approximate randomization) accounts for correlation and variance:

- Paired \(t\)-test: Compare metric differences per example across systems.

- Randomization: Shuffle system outputs to simulate null hypothesis.

- Application:

- Dror et al. (2017) recommend testing across multiple datasets for robustness.

Statistical significance testing is essential for validating NLP experiment results. (7/8)

Proper significance reporting ensures replicability and trust in classification experiments.

- Reporting standards include:

- Declaring test set size, number of runs, and test statistic used.

- Reporting confidence intervals, not just point estimates.

Statistical significance testing is essential for validating NLP experiment results. (8/8)

Replicability crisis in NLP highlights the necessity of statistical rigor.

Example reporting statement:

- “System A outperforms System B on F1 (\(p = 0.03\), 95% CI: [0.02, 0.08]) across 10 datasets.”

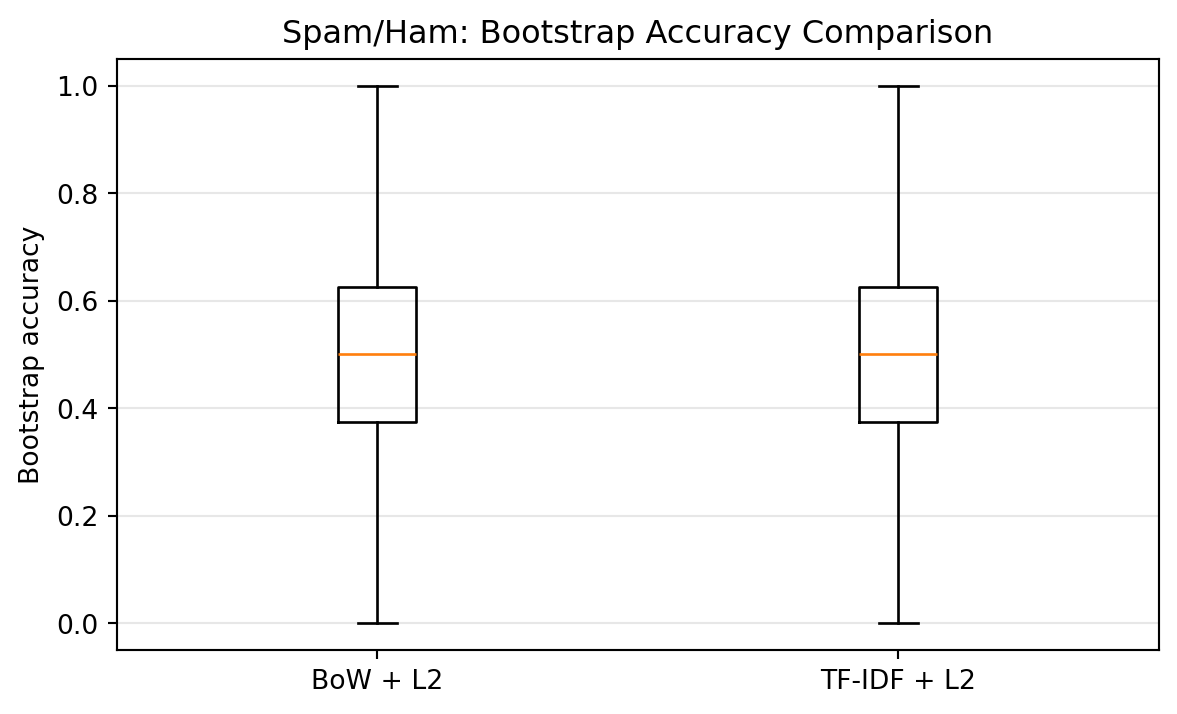

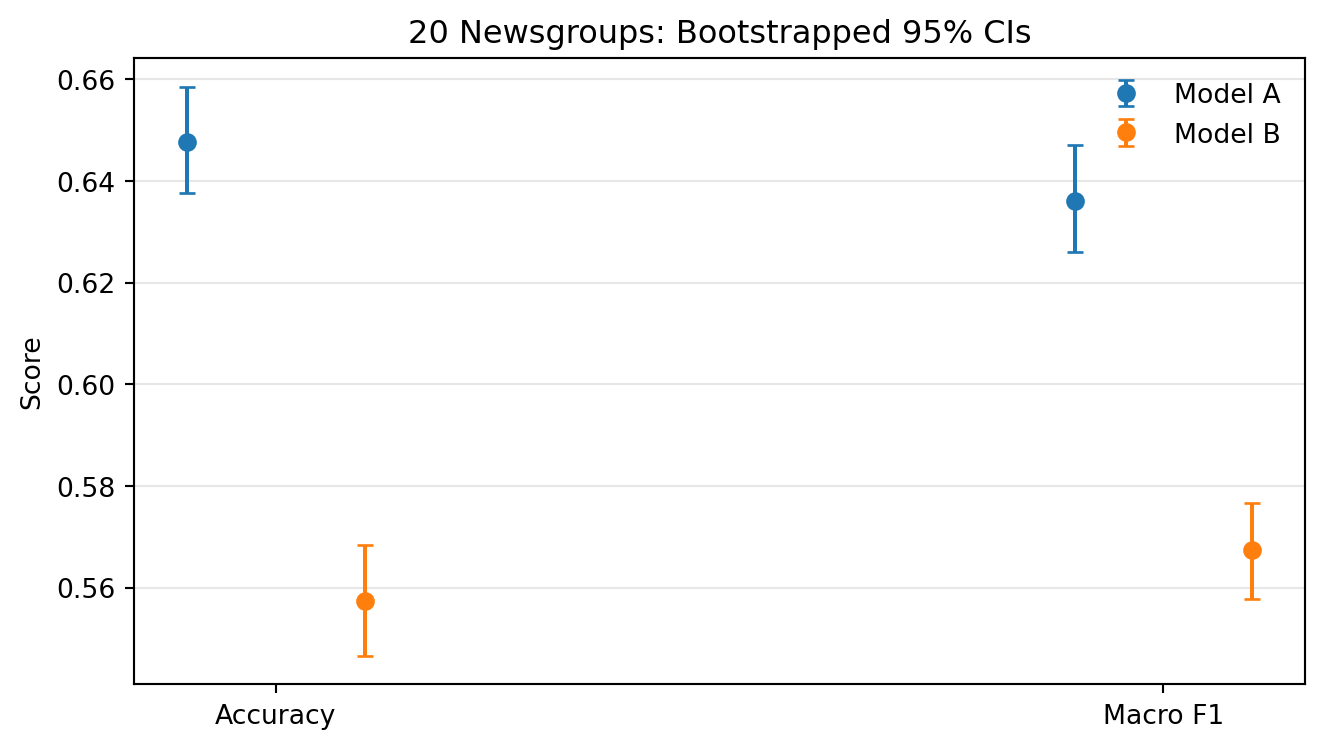

Bootstrap comparison: spam/ham text models

- Model A: Bag-of-words counts + L2 logistic regression.

- Model B: TF-IDF unigrams + L2 logistic regression.

Part 4: Case Study: 20 Newsgroups Classification

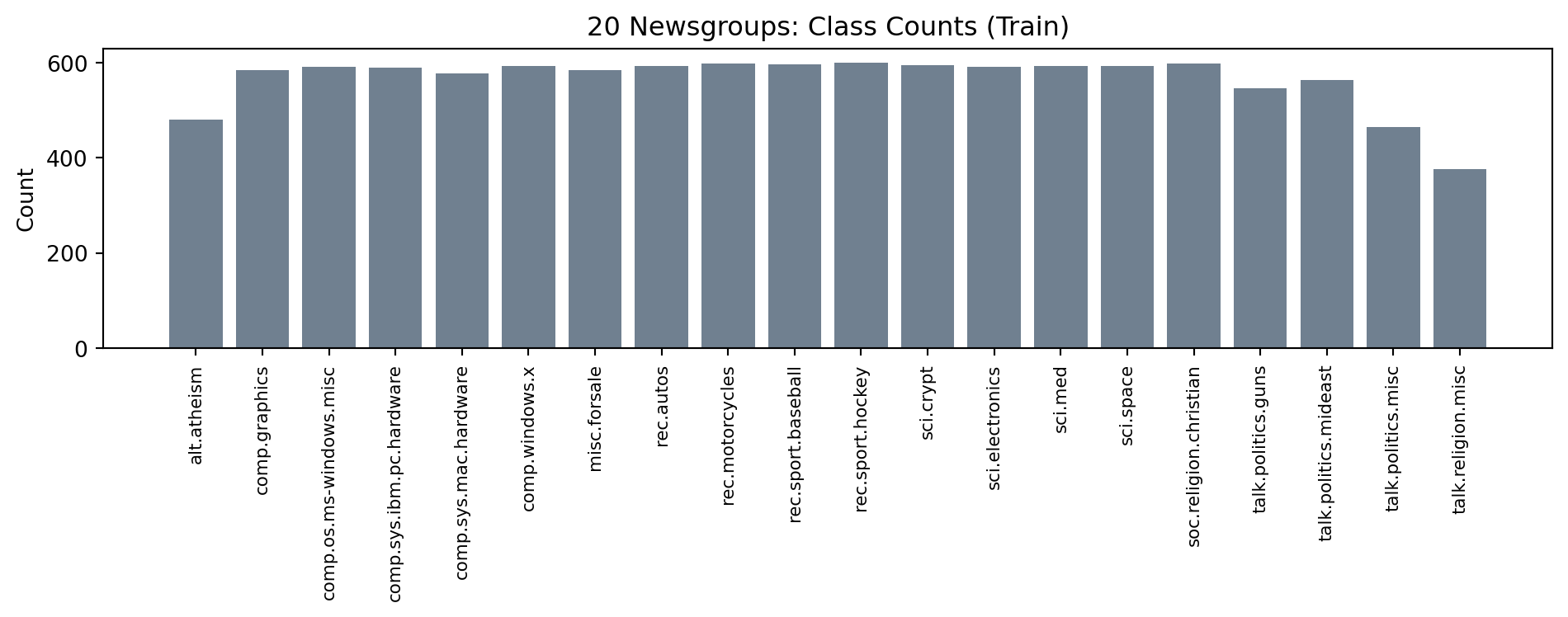

20 Newsgroups: classification task

- Predict the discussion group label from the post text.

- Usenet posts from 20 topical forums (sports, politics, tech, religion).

- 20 categories, balanced enough that accuracy is meaningful.

- We strip headers/footers/quotes to focus on content.

Dataset overview

- Train/test splits come from scikit-learn’s

fetch_20newsgroups. - Each example is a short, noisy, user-generated post.

Train size: 11314 Test size: 7532

Classes: 20Example posts (truncated)

- Look for topical keywords that hint at the group label.

[rec.autos] I was wondering if anyone out there could enlighten me on this car I saw the other day. It was a 2-door sports car, looked to be from the late 60s/ early 70s. It was called a...

[comp.sys.mac.hardware] --

[comp.graphics] Hello, I am looking to add voice input capability to a user interface I am developing on an HP730 (UNIX) workstation. I would greatly appreciate information anyone would care to...

Bigram example: phrase cues

- Bigrams capture short phrases (e.g., “space shuttle”, “power supply”).

Example bigrams: ['60s early' 'info funky' 'know tellme' 'late 60s' 'looked late'

'looking car' 'model engine' 'production car' 'really small' 'saw day']Class distribution (train split)

- Classes are roughly balanced, but not perfectly uniform.

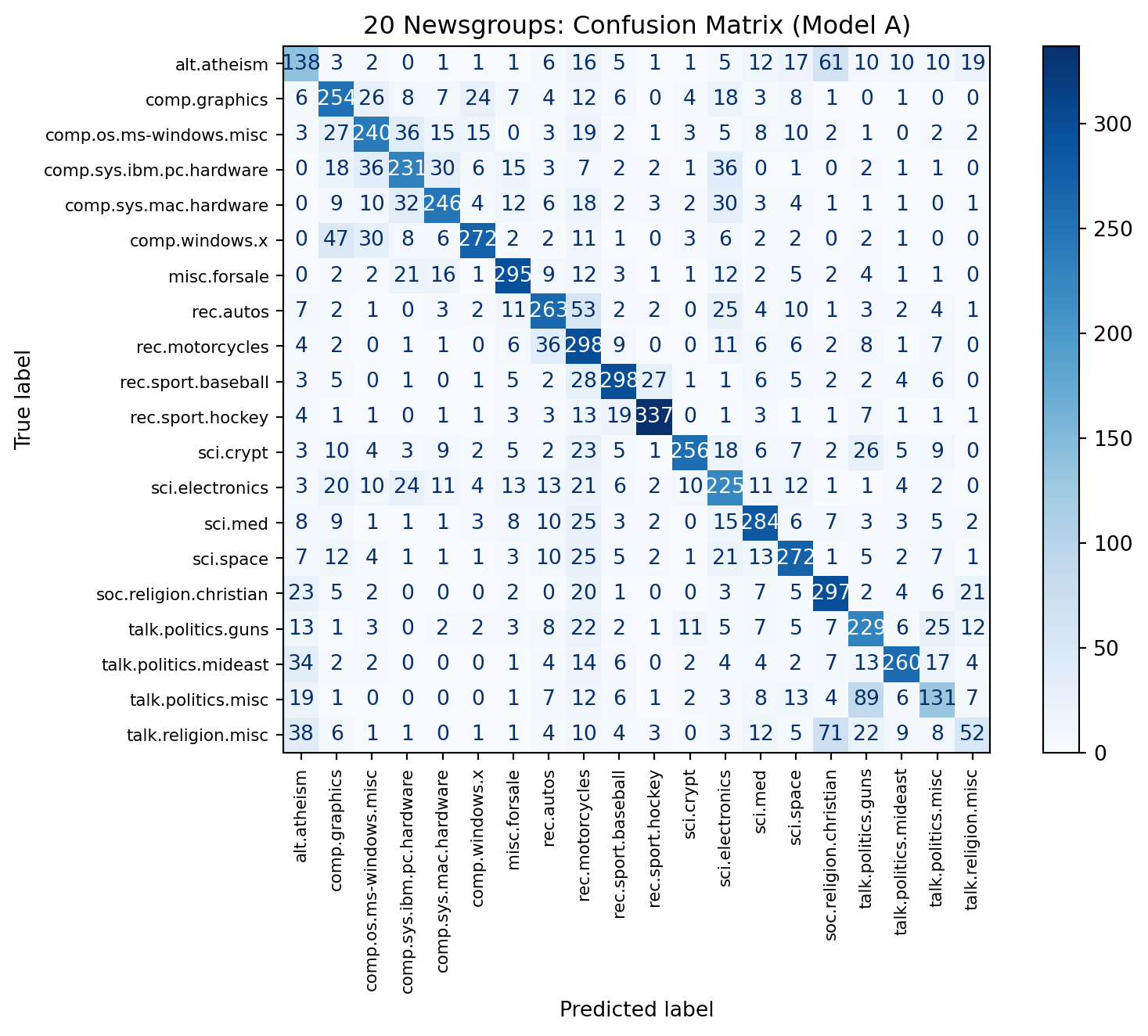

Model A: TF-IDF unigrams + L2 logistic regression

- TF-IDF reduces weight on common terms.

- L2 regularization discourages overly large weights.

- Strong baseline with relatively compact feature space.

Model B: TF-IDF unigrams+bigrams + L1 logistic regression

- Bigrams add short-phrase cues.

- L1 encourages sparse, feature-selective weights.

- More features, higher risk of overfitting on small topics.

Accuracy + micro/macro precision/recall/F1

- Micro averages track overall correctness; macro highlights per-class balance.

- Micro: pool all predictions, then compute global \(P/R/F_1\) from total TP/FP/FN.

- Macro: compute \(P/R/F_1\) per class, then average (each class equal weight).

Model A: acc=0.648

micro: P=0.648 R=0.648 F1=0.648

macro: P=0.650 R=0.635 F1=0.636

Model B: acc=0.557

micro: P=0.557 R=0.557 F1=0.557

macro: P=0.619 R=0.546 F1=0.567\(F_\beta\) emphasizes recall when \(\beta > 1\)

- Example: \(F_2\) weights recall higher than precision.

- Useful when missing a topic is costlier than a false alarm.

Model A F2: 0.634

Model B F2: 0.550Confusion matrix (best macro F1)

Bootstrapped confidence intervals

- 95% CIs for accuracy and macro F1.

- Overlapping intervals would suggest weak evidence of a difference.

Model comparison takeaways

- Model A is a strong, simple baseline with fewer features.

- Model B adds phrase cues but can trade speed for sparsity.

- Macro metrics and the confusion matrix show where each model struggles.

CSE 447/517 26wi - NLP